Underlying research behind the PFAS standards for reuse of soils and sediments

There was considerable social unrest regarding significant restrictions in the recycling of soil and dredged material due to the presence of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). The temporary operational framework of July 2019 did not offer a sufficient solution. Incrementally (November 2019, July 2020), standards were further elaborated, so that recycling is now largely possible again. Under considerable timepressure, RIVM (the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment) and Deltares have derived limit values in order to enable this. This article is about the underlying studies and analyses behind the new PFAS standards.

Applying soil and dredged material in surface water has been regulated in the Decree and Regulations on soil quality (Soil Decree). This decree is especially aimed at a fast and routine test to determine whether the reuse of soil and dredged material is environmentally acceptable and whether there is a question of deterioration in the (water) soil quality. The routine character is expressed in a recorded substance list and generic standards, for instance.

PFAS, a collective name for more than 6,000 substances in which, for instance, a combination of fluor compounds and alkyl groups occur, did not appear on the substance list, while perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) had meanwhile become a priority substance in the Water Framework Directive (Kaderrichtlijn Water). The Soil Decree does not provide a simple option for adding new substances. However, a duty of care does apply, also in situations where no specific statutory regulation has been violated. After a few incidents (Schiphol, Chemours), more research was carried out into PFAS. This showed that these substances did not occur incidentally, but were dispersed.

Based on the duty of care, it was therefore argued that it would only be possible to recycle soil and dredged material if they could be shown not to contain any PFAS. A decree with considerable consequences, the soil removal and dredging activities stagnated. In order to fulfil the duty of care, in July 2019 the first version of the Temporary operational framework PFAS was published. Due to a lack of knowledge, the determination limit (0.1 µg/kg) remained the upper limit for most applications in surface water. The stagnation was not resolved with this.

For this reason, the Temporary operational framework was amended incrementally in November 2019 and in July 2020. In this way, on the basis of additional research and policy development, a responsible expansion of the application standards was worked on. This article describes the studies which were used as substantiation for the applications: 1. The new background value (AW) soil (Wintersen et al., 2020a), 2. A recontamination level (herverontreinigingsniveau (HVN)) in the large national waters (Osté et al., 2019), 3. An HVN in regional waters (Osté, 2020) and 4. The differences in the leaching of PFAS from soil and dredged material (Wintersen et al., 2020b).

Background value soil

Once it was known that PFAS were diffusely distributed in all soiland sediments in the Netherlands, it was therefore clear that background values had to be established for this group of substances, as had been carried out in the past for other diffuse substances in the soil (Lamé et al. 2004). In order to obtain these values available as soon as possible, the unconventional step was taken to determine temporary background values on the basis of data available up until then.

In this way, it was already possible in late 2019 to determine provisional or temporary background values for two PFA compounds, namely PFOS and PFOA (0.9 and 0.8 µg/kg). Because it cannot be ruled out that the samples supplied were contaminated, the decision was made not to determine the temporary background values with the customary 95th-percentile value (P95 1) of concentrations, but with a cautious P80.

In mid-2020, the final background values were published on the basis of a new soil survey covering the entire country (Wintersen et al., 2020a). Since this survey was exclusively carried out at carefully selected agricultural and nature locations, this time the P95 could be used. This ensured an expansion compared with the temporary background values for PFOS and PFOA (1.4 and 1.9 µg/kg). Furthermore, it appeared that no other (of the thirty analysed) PFAS compounds were found structurally in the soil.

In 2007, it was decided that the background value for soil (the ‘always clean’ limit) also applied to sediments. Generally, the background value is lower than the recontamination level (HVN), but for PFOA this did not appear to be the case. This is why the background value for soil for PFAS were pronounced not applicable to the water bed.

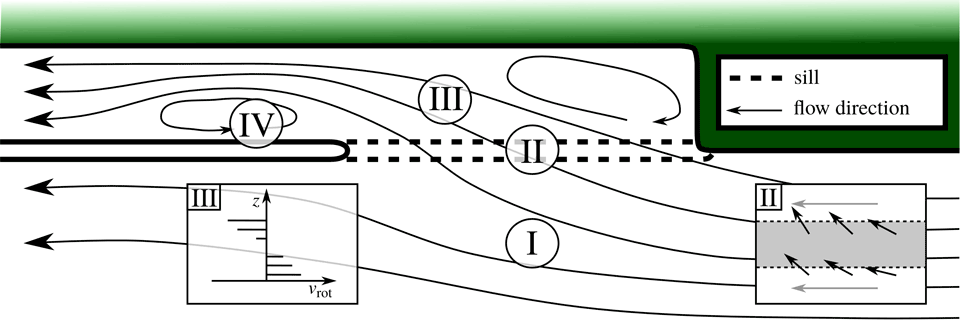

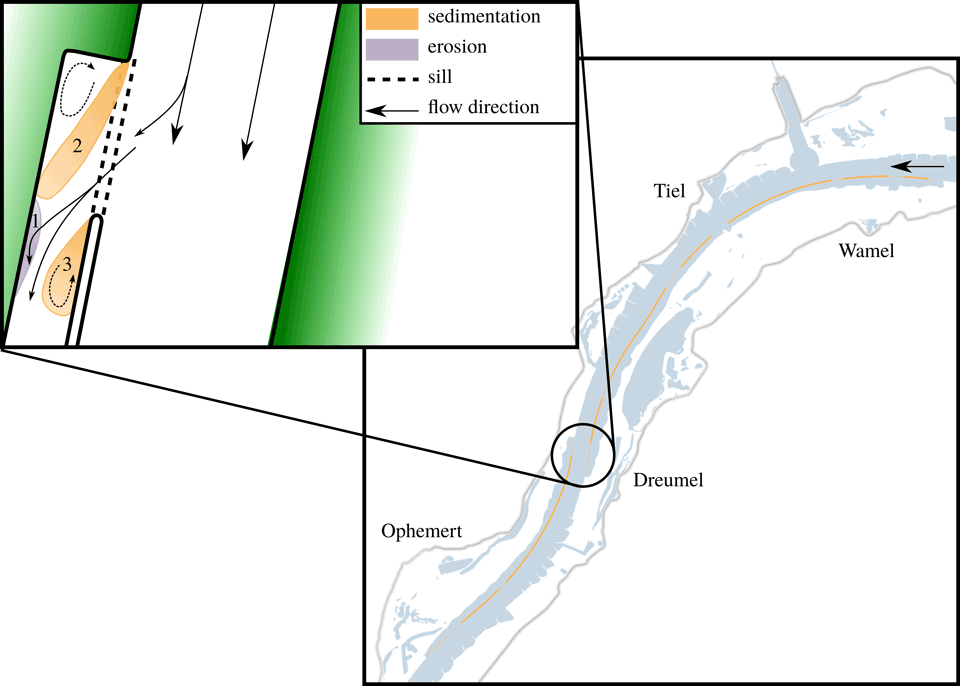

Recontamination (HVN) of national waters

Since the standstill principle is an important pillar of the Decree on soil quality, the HVN Rhine catchment plays a vital role. It was pronounced applicable to the whole of the Netherlands, so also in the regional waters and in the other Dutch river basins. The HVN Rhine catchment is calculated by determining the 95th percentile of ten years of suspended particulate matter quality at the Lobith measurement station, where the Rhine enters our country. However, PFAS were not measured in suspended particulate matter. When the debate about PFAS occurred, RWS added PFAS (thirty substances) at twenty monitoring locations in the national waters to the list of compounds.

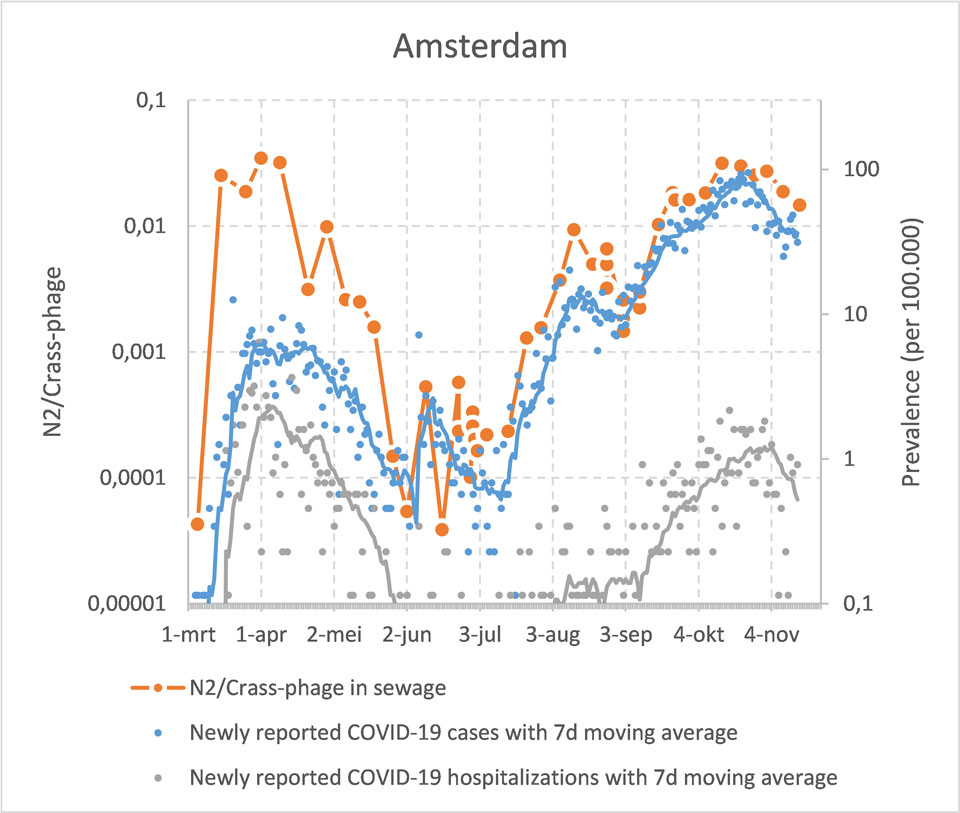

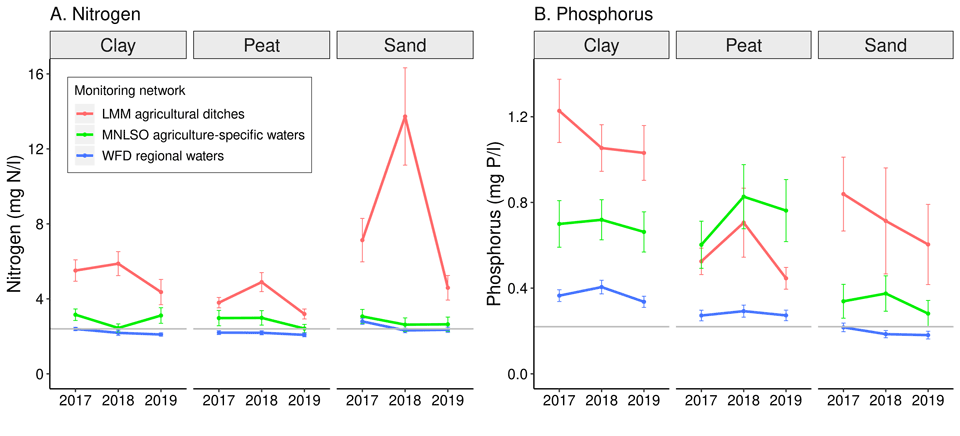

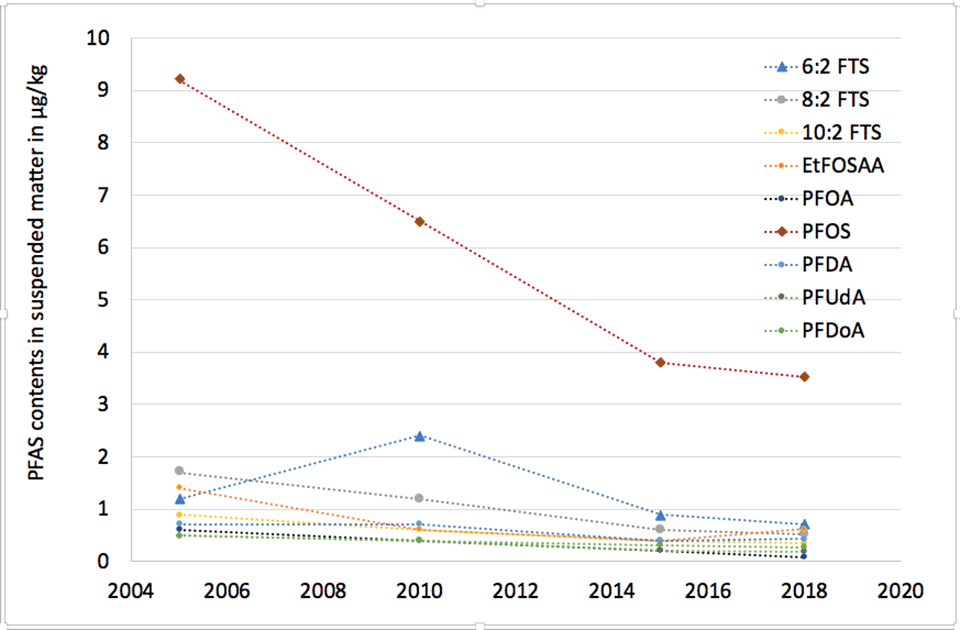

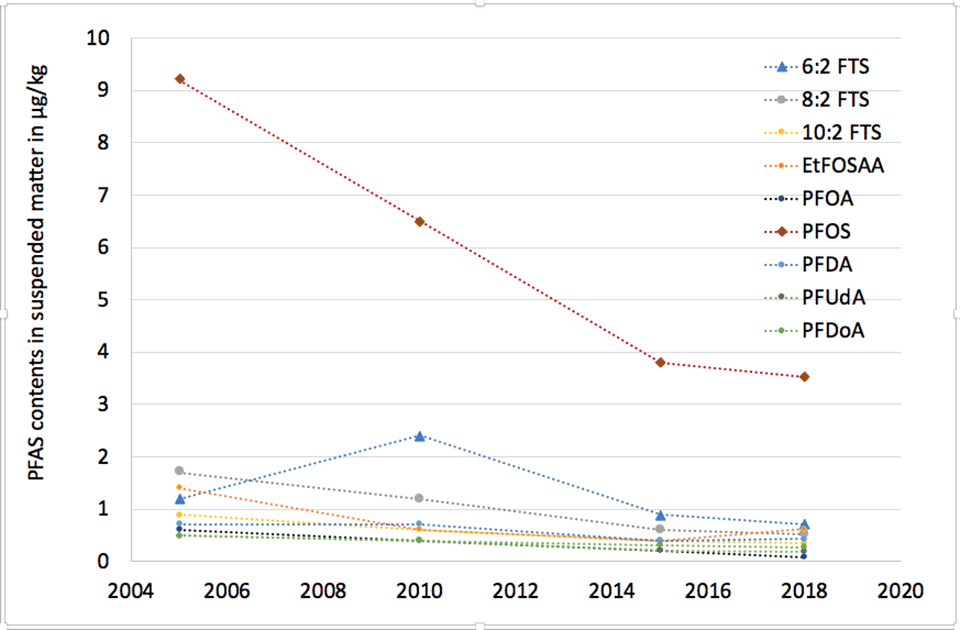

The temporary HVN national waters for PFAS were determined on the basis of these measurements. An 80th percentile was chosen, as a ten-year series was not available, comparable with the percentile that had been chosen for the temporary background values soil. For PFOS that rule was deviated from because, from the historical measurements, it appeared that a downward trend was observed (figure 1). The data used already contained relatively low levels compared with a ten-year series. The precaution of an 80th-percentile value would lead to a ‘double precaution’. This is why a 95th percentile was chosen for PFOS.

The above-mentioned methodology ultimately resulted in an HVN for PFOS of 3.7 µg/kg. In contrast to soils, also other PFAS than PFOS and PFOA were found in sediments. These PFAS compounds were all under 1 µg/kg. The highest of those ‘others’ (EtFOSAA: 0.8 µg/kg) was pronounced applicable to all other PFAS.

Figure 1. Trends of average PFAS levels in suspended matter in national waters

Figure 1. Trends of average PFAS levels in suspended matter in national waters

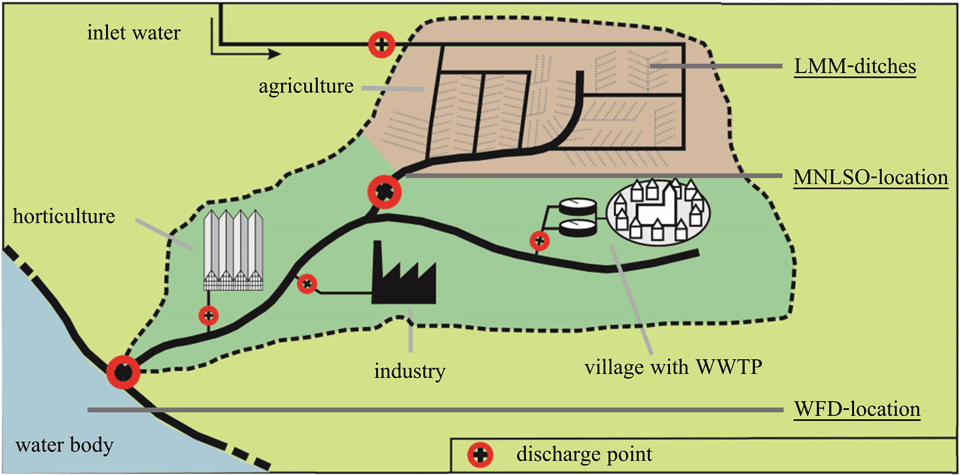

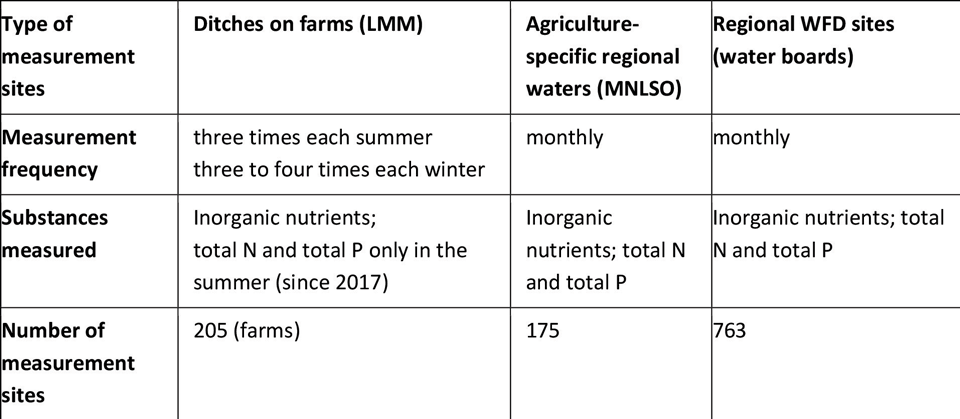

HVN regional waters

Since the implementation of the Soil Decree, the redesign of deep lakes using soils and sediments, had really taken off, also in regional waters (often not connected to other surface water). For this purpose, the maximum value class A (HVN Rhine catchment) applies as a generic standard. The question was therefore whether HVN national waters for PFAS was also suitable for lakes outside the national waters. On the basis of a database of PFAS in regional water beds, it appears that the HVN national waters is higher than the sediment quality in the regional waters.

The HVN national waters would not guarantee a standstill in regional waters and therefore, in late 2019, it was pronounced only applicable to lakes in a direct connection with the national waters where redesigned had already commenced. In order to accommodate the redesign of regional lakes already in process, in spring 2020, it was proposed to derive for this purpose an HVN for regional waters on the basis of water-bed data and not on the basis of suspended particulate matter. For various reasons, in this case an 80th percentile of all the data was also used.

Leaching of PFAS from soil and dredged material

The application of the standards for redesigning deep lakes in connection with the national waters in November 2019 was limited to with the use of dredged material. This limitation arose from the assumption that the mobility of PFAS could be different in soils, which are affected by air deposition, and wet sediment, which are exposed to direct discharges on surface water and have low-oxygen conditions.

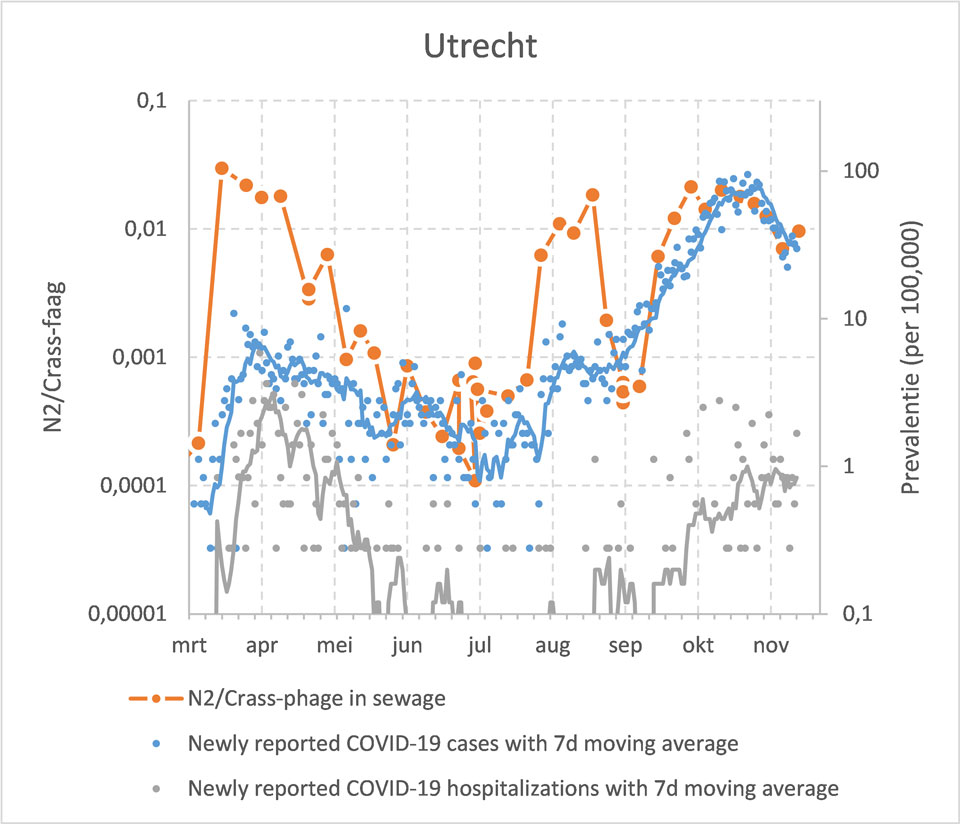

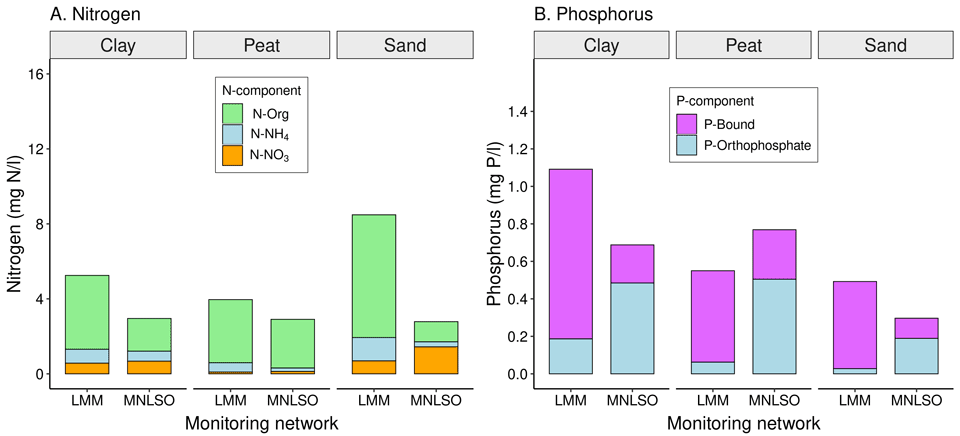

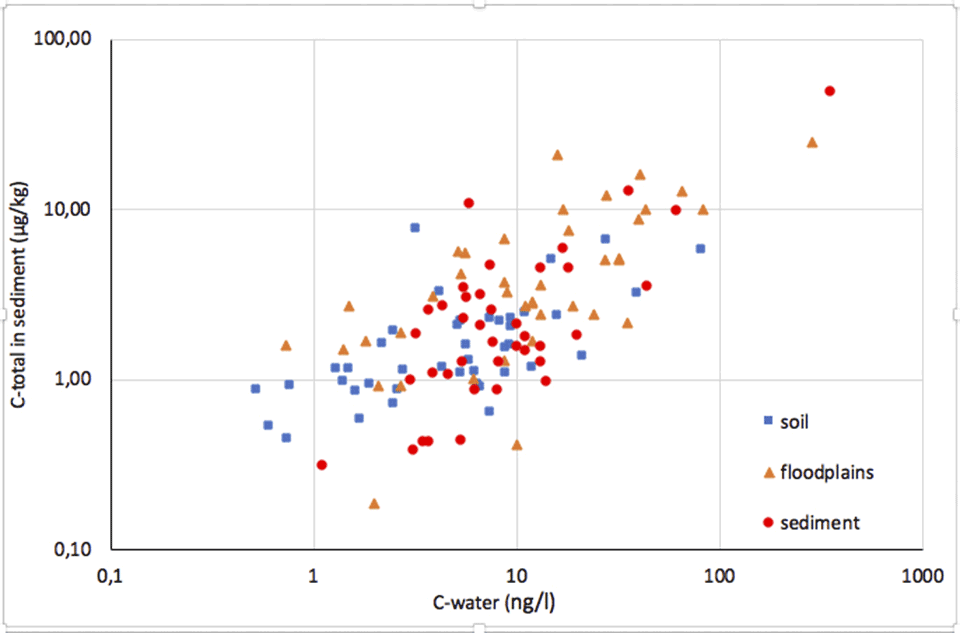

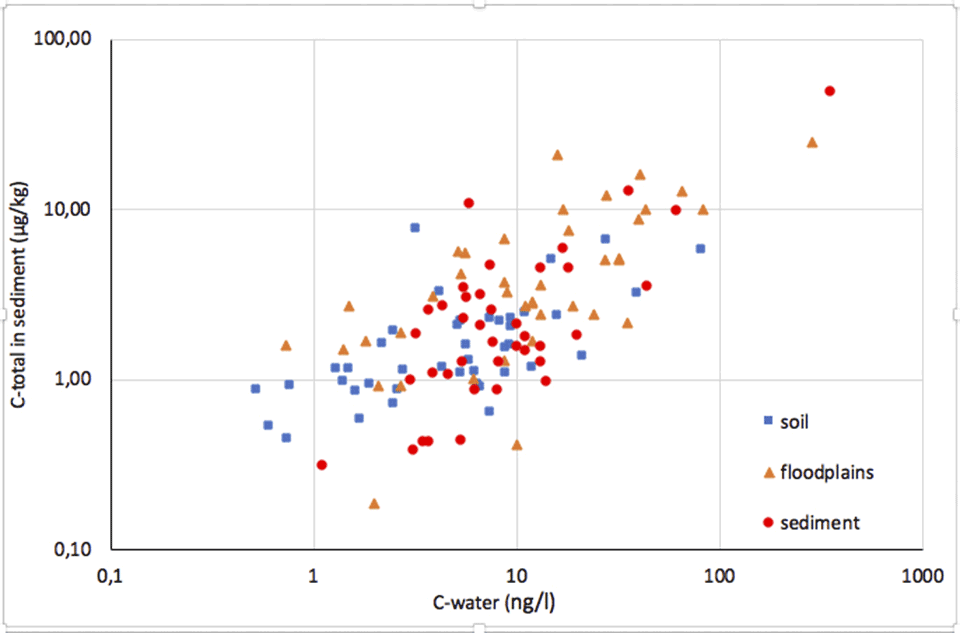

In spring 2020, research was carried out into the leaching behaviour of PFAS. Three times, forty samples were examined of the categories soil, flood plains and water bed (dredged material). The soils were shaken for twenty-four hours in a ratio of 1 (solid ground) to 10 (liquid) in accordance with ISO 21268. The solid phase and water phase were then examined for the same PFAS compounds. From the study, it appeared for PFOS and PFOA that the extent of leaching from the soil is not greater than from sediments or flood plains (figure 2). No clear relation was found between the leaching and soil characteristics such as pH, lutum and DOC. A weak relation was found between organic matter and the leaching.

Figure 2. Relationship between PFOS in the solid phase (soil, floodplain soil and sediment) and PFOS in the liquid phase of a shaking test

Figure 2. Relationship between PFOS in the solid phase (soil, floodplain soil and sediment) and PFOS in the liquid phase of a shaking test

Glance ahead:

The temporary operational framework of July 2020 will not be the last update. At present, an update of the HVN national waters is being worked on, because new data in suspended particulate matter was collected in 2020. A PFAS policy for dredged material that will be redistributed at sea is also being worked on. Lastly, it is being considered whether an upper limit for reuse can be applied, comparable to the maximum value class B.

In addition, PFAS has resulted in several discussions that also touch on other substances. Firstly, from the PFAS file, we can learn how we should approach new substances in the future. Furthermore, the question is whether an HVN regional waters should also apply to other substances, and the coordination of the earth removal with the Framework Directive Water requires further attention. Such discussions require time and will not be resolved within the definitive PFAS action framework.

Leonard Osté

(Deltares)

Arjen Wintersen

(RIVM)

1 In a distribution, 95% of the observations lie under the P95 value. The background values provide an indication of the top level of the concentrations that can be found in unsuspected areas. The choice for a P80 results in a lower value.

Summary

After a few incidents (Schiphol, Chemours), more research was carried out into perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). This showed that these substances did not occur incidentally but were diffusely dispersed. However, PFAS did not appear on the substance lists of the Decree on soil quality. Based on the duty of care, it was therefore determined that soil and dredged material could only be applied if they were shown not to contain any PFAS. With the aid of temporary standards, the duty of care has gradually been elaborated within the temporary action framework, so that soil and dredged material removal is now largely possible again. This article addresses the underlying studies which were used to substantiate these standards. It concerns determining: 1. The new background value (AW) soil, 2. A recontamination level (herverontreinigingsniveau (HVN)) in the national waters, 3. An HVN in regional waters and 4. The differences in leaching PFAS from soil and dredged material. Finally, future developments concerning the standard construction for applying soil and dredged material in surface water are considered.

Literature

Lamé, F. P. J., Brus, D. J., & Nieuwenhuis, R. H. (2004). Background values 2000. Main report AW2000 phase 1.

Osté, L., I. van Tol, R. Berbee, W. Altena, 2019. Advice provisional recontamination level (HVN), PFAS for water beds for applying and distributing dredged material in surface water (Advies voorlopig herverontreinigingsniveau (HVN) PFAS voor waterbodems voor het toepassen en verspreiden van baggerspecie in oppervlaktewater). Deltares report 11203697-018-BGS-0001.

Osté, L. 2020. Recontamination of PFAS in dredged material from regional waters (Herverontreinigingsniveau PFAS in bagger uit regionale wateren). Deltares memo 11205535-006.

Wintersen, A., J. Spijker, P. van Breemen, H. van Wijnen, P. Otte 2020a. National background values soil for PFOS and PFOA (Landelijke achtergrondwaarden bodem voor PFOS en PFOA). RIVM report 2020-0100.

Wintersen, A. Osté, L., R. van der Meiracker, P. van Breemen, G. Roskam, J. Spijker, 2020b. Difference in leaching of PFAS from soil and dredged material (Verschil in uitloging van PFAS uit grond en bagger). RIVM report 2020-0102.

^ Back to start